I say a sad goodbye to Anna, her son Christopher and Sonali, our neighbor from the village, and travel by rickshaw to the appointed place on the side of the road where I will board an overnight bus. Here I part with Neil, who has helped me with my luggage, barely manageable with the impressive weight of my books. The first hour of the bus trip is taken up by negotiations over seats. In acknowledgment in part of the male groping of unescorted females that is pervasive here, buses have ‘ladies seating.’ On this better class of bus, if one has been assigned a seat to a man, as I was, one can ask for ‘ladies seating’ and the driver or his assistant will generally shuffle people around until you are either alone or next to another woman. Since I have been ordained, I appear to be exempt from Another woman is also insisting on ladies seating, and at last we end up seated together. We arrive a few hours after dawn in Hyderabad, where Sangeeta awaits me with another rickshaw. I spend two extremely relaxing days in this very cosmopolitan city and then there’s another overnight ride, this time by train, to reach Visakhapatnam.

Here I am now, in a parallel scholarly universe to Pune. Here there are no trappings of scholarly achievement, no ivy-covered institutes, no titles on the door: just Shastry Garu, my Sanskrit teacher from Madison, now returned back at his home in Visakhapatnam. He resumes his role as a teacher fiercely committed to his vision of Sanskrit study, and we read from 9 in the morning until 10 or 11 at night, with intermittent breaks through the day. Already in the first five days we have read more than the scholar in Pune and I managed to go through together in two months. This is very good. When not reading Sanskrit, memorizing verses form the text or preparing a draft translation of what we have read, I eat and sleep in a ‘ladies hostel,’ which is basically off-campus dormitory housing, very basic housing that I share with young Indian ‘ladies,’ mostly undergraduates away from home for the first time. On all this, more later.

Saturday, June 17, 2006

Monday, June 12, 2006

time to go

After two months in Pune, it is time to go. I was planning on passing the monsoon here, working on the Sanskrit edition of my text, but will leave three months ahead of plan, not because I have completed my work, but because I have not, or at least not much of it.

After agreeing to read with me, the Indian scholar I had come to work with was offered the highly visible and highly prestigious position of executive director of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute -- a position that has left him little time for me and my little project. Though he seems interested in the text, he regularly has to cancel our meetings, and our progress has often ground to a halt as he deals with his administrative duties.

In this way, two months pass, and I now find myself leaving Pune having covered only 11 pages with the scholar-turned-administrator. 11 pages. Of a 400-page Sanskrit text. this is very bad.

I call my dissertation adviser, Charles Hallisey, to see about applying for a grant for a second year of research, since obviously at this rate, one would not be enough. (Actually at the rate we have maintained here, 30 years would not be enough!) My adviser’s response: ‘You are telling me you are not making progress there and so you want to spend more time there? Move on. See if Shastri in Visakhapatnam will read with you.’ I call my Sanskrit teacher Shastri Garu and he says, come. Come soon. He is planning to travel to the States and may leave in a few weeks or months.

As I hope this blog shows, Pune is a fascinating and highly livable town. It just has not been an enormously productive one for me. I book my tickets and prepare to leave Pune.

After agreeing to read with me, the Indian scholar I had come to work with was offered the highly visible and highly prestigious position of executive director of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute -- a position that has left him little time for me and my little project. Though he seems interested in the text, he regularly has to cancel our meetings, and our progress has often ground to a halt as he deals with his administrative duties.

In this way, two months pass, and I now find myself leaving Pune having covered only 11 pages with the scholar-turned-administrator. 11 pages. Of a 400-page Sanskrit text. this is very bad.

I call my dissertation adviser, Charles Hallisey, to see about applying for a grant for a second year of research, since obviously at this rate, one would not be enough. (Actually at the rate we have maintained here, 30 years would not be enough!) My adviser’s response: ‘You are telling me you are not making progress there and so you want to spend more time there? Move on. See if Shastri in Visakhapatnam will read with you.’ I call my Sanskrit teacher Shastri Garu and he says, come. Come soon. He is planning to travel to the States and may leave in a few weeks or months.

As I hope this blog shows, Pune is a fascinating and highly livable town. It just has not been an enormously productive one for me. I book my tickets and prepare to leave Pune.

monasteries built in stone

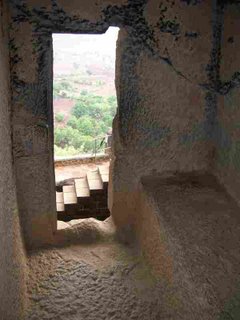

An easy day-trip from the city of Pune are two sets of Buddhist cave complexes, at Bhājā and Karlī (now known as Karla). I could flat-footedly describe them as monasteries carved out of the mountains, but what was important about visiting here will be harder to convey. I will try, but first, some basic facts: These elaborate structures were built by removing rock from the mountain, leaving in place large open spaces, some with high arched ceilings, dramatic colonnades and some lovely wall-carvings.

At both complexes, the long vaults of teak wood that decorate the ceiling of the central hall are said to be original. But especially what the artisans made of these mountains were monastic living quarters. About half the caves were monastic residences.

Buddhist monks first moved in to them some 2,100 years ago, according to archeologists who date the sites to the two centuries before the common era (160 BCE and 80 BCE are dates commonly given). In some cases, living quarters are carved out of the walls of a large gathering space; in some cases there are multiple stories of quarters, usually quite tiny, connected by winding stairways of stone.

Buddhist monks first moved in to them some 2,100 years ago, according to archeologists who date the sites to the two centuries before the common era (160 BCE and 80 BCE are dates commonly given). In some cases, living quarters are carved out of the walls of a large gathering space; in some cases there are multiple stories of quarters, usually quite tiny, connected by winding stairways of stone.

It is hard to fathom the effort it must have taken to wrest these elaborate spaces from the rock, but the strategic placement of these complexes is confirmed by the sight of two long stone forts built at the peaks of two surrounding passes. I made the trip to visit these caves recently with Neil Dalal, another Fulbrighter here in Pune. Neil is a deeply thoughtful student of Vedanta, and made a wonderful traveling companion for this excursion.

There is something extraordinary that can happen simply being by physical present at places that were important to the people who occupied them. Not always, but sometimes, and sometimes this ‘something’ defies our ordinary understanding of the shape of time, and this is especially so if one knows that one is in a place lived in for long periods of time in the past by humans for whom they were deeply meaningful. At least that was the case for me here.

There have been times in Pune - not a city in which Buddhist monks are likely to be seen wandering - when my own monastic robes and vows have seemed out of context. Without a context - a context that most often is provided simply by being in a Buddhist community - the purpose and meaning of those vows can easily lose its clarity. Sitting here, even without any other actual members of the monastic community, that context was fully present for me.

These Buddhist sites caves apparently do not see many visitors most days, though those who do come seem unusually interested in shouting into the caves for the acoustic effect. A temple to the goddess Ekvira, built literally at the doorstep of the main Buddhist cave, draws Hindu pilgrims, but these seldom seem to visit any but the largest Buddhist cave. Across the valley, Bhājā was nearly deserted when we arrived, save for two elderly attendants. Here, Neil and I were each able to take a good stretch of time to just sit silently, each in our own monastic cell.

In one of the photos that I will be posting towards the bottom of this blog entry, you can see the bed (or so I understand it) of rock left in the cell when the rest was carved out. Removing my shoes and entering, I sat down where some other monk must surely have sat in a past I can only reach in my imagination. Actually, since the caves were in use for many centuries, dozens of generations of monks certainly must have sat there. In my robes, holding vows that may have passed received through their lineage, I sat and tried to connect with the other monks who sat there, perhaps arguing with their friends, meditating, reading, sleeping, or like me resting my eyes on the long and lush green view out the door to the cell, wondering about others who had been there before. Or perhaps they wondered about those who would come in the future, in their future that was now my present. Nurturing, protecting and transmitting the teaching of the Buddha as a way of caring for future generations is a prominent part of some Buddhist practices, as is cultivating gratitude for those who have done so for you in the past. And so the monks and I sat in those small quarters, wondering about each other, caring for each other and feeling thankful for the care received.

Sunday, June 11, 2006

the bus that means death

One day after a heavy rain, there is a death in the family whose wedding puja I had just attended. Shortly after the wedding, they awake to find that their grandather’s sister had passed away in the night. She has been living in the household for years, but the night before she said she felt unwell, and asked that her older brother be called. He was on the other side of the city visiting a clinic with his wife, who has also been ill. He is located and comes at once to see his younger sister. They spend a short time together, and then she rests. By morning her long life has ended.

She was frail and old, and always smiling, my neighbor Anna tells me. When news of her death comes early in the morning, Anna dresses at once and goes ‘to say goodbye.’ The grandfather’s sister is laid out for viewing in the house, her nostrils and mouth plugged with some bit of cloth. Bodies here are cremated as soon as possible, generally the same day, and we are told she will be taken from the house for cremation in a couple of hours. Word spreads quickly, and the neighbors and family in the area come immediately to bid her farewell.

Later, as I am leaving my room, I see a white bus marked with a large red cross on its way out of the institute. Her body has been placed inside. The bus has no glass windows, just grills, and is filled with relatives of the deceased, accompanying her body. Others who will not go the cremation ground walk along behind the bus, seeing it off to the main road. I join them. Only one face is trailed with tears, a young woman. The rest are subdued but calm. We soon reach the gate, where the relatives remaining behind will part company with the deceased.

Everyone knows what this bus means. “Who has died?” the staff who are just now arriving at the institute ask us. We tell them. They nod, and stand beside us in silence as we all watch the bus pass on to the next leg of its journey.

She was frail and old, and always smiling, my neighbor Anna tells me. When news of her death comes early in the morning, Anna dresses at once and goes ‘to say goodbye.’ The grandfather’s sister is laid out for viewing in the house, her nostrils and mouth plugged with some bit of cloth. Bodies here are cremated as soon as possible, generally the same day, and we are told she will be taken from the house for cremation in a couple of hours. Word spreads quickly, and the neighbors and family in the area come immediately to bid her farewell.

Later, as I am leaving my room, I see a white bus marked with a large red cross on its way out of the institute. Her body has been placed inside. The bus has no glass windows, just grills, and is filled with relatives of the deceased, accompanying her body. Others who will not go the cremation ground walk along behind the bus, seeing it off to the main road. I join them. Only one face is trailed with tears, a young woman. The rest are subdued but calm. We soon reach the gate, where the relatives remaining behind will part company with the deceased.

Everyone knows what this bus means. “Who has died?” the staff who are just now arriving at the institute ask us. We tell them. They nod, and stand beside us in silence as we all watch the bus pass on to the next leg of its journey.

Thursday, June 08, 2006

a walk amongst pune’s ‘outsiders’

One evening while riding in a rickshaw with my friend Kranti, I spotted first what looked to me like a Hindu shrine temple with Muslims entering it, and then a large structure that looked like a Catholic church but which she told me was a synagogue. I was intrigued, and she promised to take me to see them both one day. When that day comes, along the way within minutes, we pass a magnificent Jain temple, several Buddhist ‘vihāras’ or tiny temples that also look on the outside very much like the Hindu temples that dot the urban landscape here, a massive church of Saint Francis, a Parsi place of worship closed off to view from the street, as well as a Moslem shrine to a female saint, before reaching finally the city’s oldest Jewish house of worship (see separate blog entry on this). This extravaganza of religious pluralism, ironically enough, turns out to be a by-product of the exclusivist impulses of Pune’s brahmin community.

I chose to come to Pune in part because it is a major center of Sanskrit learning. I am told that many generations back, a king eager to attract brahmins to his kingdom offered land grants to any who would come and settle in ‘the village of Pune,’ as those with long memories still call this now bustling city of Pune. Many took up the offer, made their homes alongside the purifying waters of the town’s broad rivers, and established Pune as a stronghold of brahminical culture and learning. It is still today a great place to come to study that culture’s lifeblood, the Sanskrit language. Brahmins’ status as brahmins depended on maintaining ritual purity. The necessary distance from potentially polluting factors was upheld physically as well as socially. As such, those who are not members of one of the upper castes were discouraged from making their homes within the boundaries of the heavily brahmin Pune village. Even today, it is within the ‘village’ of Pune that brahmins and members of the upper three Hindu castes tend to make their homes. And for generations now, everyone else - Jews, Jains, Christians, Muslims, Parsis, as well as members of those Hindu groups once called ‘outcaste’ or ‘untouchable’ - has made their homes outside that central area of Pune, and away from the pure waters of the city’s two rivers.

It in this outsider’s zone that all the diverse places of worship are clustered, and where those whom they serve live shoulder-to-shoulder. Indeed, it was in this outsider’s area that the British encamped, earning it the name of ‘Camp,’ or, more formally, Pune Cantonment. These boundaries are important, and even today, there are signs in English and Marathi announcing when one is entering or exiting ‘Pune Cantonment.’

My walk among Pune’s outsiders begins with a meal at my friend Kranti’s home. Kranti calls her neighborhood a ghetto, and as in many ghettos, much of life takes place on the street. People are washing dishes at open taps, scolding children, chatting with neighbors. For the first time in Pune, I pass elderly women, children, and young men, who brighten at the sight and place their palms together in respect for a passing Buddhist monk. Kranti’s parents followed the great Dalit leader Dr. Ambedkar in converting to Buddhism and the neighborhood is full of people who recognize my robes. The neighborhood is full of Muslims, recognizable from their manner of dressing, and Buddhists, not visibly marked as such. Kranti’s father tells me there several ‘viharas.’ Vihara is a term meaning Buddhist monastery, and I am somewhat crestfallen to see that here, a vihara is a neighborhood shrine, neatly kept swept but otherwise empty except for a simple image of Buddha and a few plastic flowers. Monasticism, as I will soon learn, has not found much favor among Ambedkari Buddhists.

We continue on. Squeezed between two storefronts is a gleaming white tower of marble, a Jain temple covered in statues and decorative ornamentation from the ground straight up to the top of its three or four stories. It is as narrow as the surrounding buildings, but magnificent, and the opus is apparently not yet complete. A group of men cluster on scaffolding, painting on one of the few unsculpted patches of wall. I wonder why I thought a camera would not be necessary to me this year in India, Kranti comments that they have a lot of money, and we move on.

Next we arrive at the Muslim shrine I mistook for a Hindu temple. The loud music and crowds outside announce to us that we have turned up on a festival day. No one seems to mind our entering, though my robes and shaven head and Kranti’s short hair and jeans might seem to mark us as well outside the fold. We remove our shoes and follow a group of women inside.

The centerpiece of the shrine is a grave, draped in gold silky fabric, covered with flowers and enclosed by a marble railing. Large photos on the wall identify the deceased as a saint named Babajan, a woman with matted hair seated at the base of a tree. Apparently she came from Afghansitan, where she was born, and spent the later years of her life at the base of that tree. Behind the grave is that very tree, also draped in gold fabric, covered with flowers and enclosed. The tree lies on the more spacious men’s side of this shrine, so we cannot pay our respects to it.

Greatly revered for her sanctity (and honored today with her own entry in Wikipedia), Babajan passed away earlier this century, and today is her birthday. Devotees buy flowers and packets of puffed rice at the entrance, hand it to a temple official standing inside the railing enclosing the tomb, who places the flowers on the grave, touches the rice to the grave and hands it back. One woman in her forties takes her rice packet and hands bits of the blessed rice to each of the other women in our part of the temple, including Kranti and me. Women lift their children over the railing so they can place their heads against the grave, sharing in its sanctity, demonstrating their reverence and receiving blessings. After one boy’s feet touch the grave, the temple official begins to do the lifting, holding them horizontally in the air, feet far from the grave. A young Muslim girl is visibly distraught to be swung into the air in this way by an unknown man, and casts her gaze about wildly, seeking her mother. A middle-aged man is praying fervently at the tomb. Tears stream down his face. His prayers complete, he wipes the tears away, glances about and departs. I whisper a question to Kranti, and we begin to attract some attention. She tells me the women are saying we should not be there. We leave.

Next we pass a massive church of Saint Francis. It is a cathedral, really, with row after row of pews spreading in three directions from the central altar. People trickle in, pray for a few minutes, and leave. Saint Francis himself is said to have died in India, and the coastal area once controlled by the Portuguese on the east coast of India, called Goa, is still both heavily Catholic in faith and Portuguese in flavor. Sheets pinned to a column outside the church itself announce classes for children in Goan handicrafts. Signs in English on the church’s wall identify the images of the stations of the cross.

As we move on in the direction of the synagogue, we pass a closed compound that Kranti tells me is a Parsi place of worship. In the street Kranti points out an older woman dressed in Western style skirts, mid-calf and respectable for even the most conservative Sicilian town, yet glaringly out of place here. In these (and most) parts of India women beyond a certain age wear saris, which are always floor-length or, if they wish to signal their modernity, a salwar kameez (or Punjabi) with pants that fall to the ankle.

Soon we are at the syunagogue, about which more in another blog entry, and with this my afternoon in Camp is concluded. As I leave by rickshaw, I note that Camp also has its swank side. The close and vibrant streets in the part of Camp where Muslims, Jains, Catholics, Parsees and Buddhists make their home in Pune gives way to broader streets where high stone walls offer only occasional glimpses at the vast and landscaped colonial ‘bungalows’ where the more affluent outsiders of Pune village make their homes. Huge billboards advertise housing complexes complete with swimming pools, fitness centers and around-the-clock security. This world seems as foreign to the heart of Camp Kranti showed me as is the Deccan Gymkhana area where I am living. The streets again become densely packed as the rickshaw crosses out of Camp and into the heart of the old city.

Soon I will be ‘home’ at Bhandarkar Institute, one of Pune’s most venerated symbols of high brahmin culture in its fullness.

I chose to come to Pune in part because it is a major center of Sanskrit learning. I am told that many generations back, a king eager to attract brahmins to his kingdom offered land grants to any who would come and settle in ‘the village of Pune,’ as those with long memories still call this now bustling city of Pune. Many took up the offer, made their homes alongside the purifying waters of the town’s broad rivers, and established Pune as a stronghold of brahminical culture and learning. It is still today a great place to come to study that culture’s lifeblood, the Sanskrit language. Brahmins’ status as brahmins depended on maintaining ritual purity. The necessary distance from potentially polluting factors was upheld physically as well as socially. As such, those who are not members of one of the upper castes were discouraged from making their homes within the boundaries of the heavily brahmin Pune village. Even today, it is within the ‘village’ of Pune that brahmins and members of the upper three Hindu castes tend to make their homes. And for generations now, everyone else - Jews, Jains, Christians, Muslims, Parsis, as well as members of those Hindu groups once called ‘outcaste’ or ‘untouchable’ - has made their homes outside that central area of Pune, and away from the pure waters of the city’s two rivers.

It in this outsider’s zone that all the diverse places of worship are clustered, and where those whom they serve live shoulder-to-shoulder. Indeed, it was in this outsider’s area that the British encamped, earning it the name of ‘Camp,’ or, more formally, Pune Cantonment. These boundaries are important, and even today, there are signs in English and Marathi announcing when one is entering or exiting ‘Pune Cantonment.’

My walk among Pune’s outsiders begins with a meal at my friend Kranti’s home. Kranti calls her neighborhood a ghetto, and as in many ghettos, much of life takes place on the street. People are washing dishes at open taps, scolding children, chatting with neighbors. For the first time in Pune, I pass elderly women, children, and young men, who brighten at the sight and place their palms together in respect for a passing Buddhist monk. Kranti’s parents followed the great Dalit leader Dr. Ambedkar in converting to Buddhism and the neighborhood is full of people who recognize my robes. The neighborhood is full of Muslims, recognizable from their manner of dressing, and Buddhists, not visibly marked as such. Kranti’s father tells me there several ‘viharas.’ Vihara is a term meaning Buddhist monastery, and I am somewhat crestfallen to see that here, a vihara is a neighborhood shrine, neatly kept swept but otherwise empty except for a simple image of Buddha and a few plastic flowers. Monasticism, as I will soon learn, has not found much favor among Ambedkari Buddhists.

We continue on. Squeezed between two storefronts is a gleaming white tower of marble, a Jain temple covered in statues and decorative ornamentation from the ground straight up to the top of its three or four stories. It is as narrow as the surrounding buildings, but magnificent, and the opus is apparently not yet complete. A group of men cluster on scaffolding, painting on one of the few unsculpted patches of wall. I wonder why I thought a camera would not be necessary to me this year in India, Kranti comments that they have a lot of money, and we move on.

Next we arrive at the Muslim shrine I mistook for a Hindu temple. The loud music and crowds outside announce to us that we have turned up on a festival day. No one seems to mind our entering, though my robes and shaven head and Kranti’s short hair and jeans might seem to mark us as well outside the fold. We remove our shoes and follow a group of women inside.

The centerpiece of the shrine is a grave, draped in gold silky fabric, covered with flowers and enclosed by a marble railing. Large photos on the wall identify the deceased as a saint named Babajan, a woman with matted hair seated at the base of a tree. Apparently she came from Afghansitan, where she was born, and spent the later years of her life at the base of that tree. Behind the grave is that very tree, also draped in gold fabric, covered with flowers and enclosed. The tree lies on the more spacious men’s side of this shrine, so we cannot pay our respects to it.

Greatly revered for her sanctity (and honored today with her own entry in Wikipedia), Babajan passed away earlier this century, and today is her birthday. Devotees buy flowers and packets of puffed rice at the entrance, hand it to a temple official standing inside the railing enclosing the tomb, who places the flowers on the grave, touches the rice to the grave and hands it back. One woman in her forties takes her rice packet and hands bits of the blessed rice to each of the other women in our part of the temple, including Kranti and me. Women lift their children over the railing so they can place their heads against the grave, sharing in its sanctity, demonstrating their reverence and receiving blessings. After one boy’s feet touch the grave, the temple official begins to do the lifting, holding them horizontally in the air, feet far from the grave. A young Muslim girl is visibly distraught to be swung into the air in this way by an unknown man, and casts her gaze about wildly, seeking her mother. A middle-aged man is praying fervently at the tomb. Tears stream down his face. His prayers complete, he wipes the tears away, glances about and departs. I whisper a question to Kranti, and we begin to attract some attention. She tells me the women are saying we should not be there. We leave.

Next we pass a massive church of Saint Francis. It is a cathedral, really, with row after row of pews spreading in three directions from the central altar. People trickle in, pray for a few minutes, and leave. Saint Francis himself is said to have died in India, and the coastal area once controlled by the Portuguese on the east coast of India, called Goa, is still both heavily Catholic in faith and Portuguese in flavor. Sheets pinned to a column outside the church itself announce classes for children in Goan handicrafts. Signs in English on the church’s wall identify the images of the stations of the cross.

As we move on in the direction of the synagogue, we pass a closed compound that Kranti tells me is a Parsi place of worship. In the street Kranti points out an older woman dressed in Western style skirts, mid-calf and respectable for even the most conservative Sicilian town, yet glaringly out of place here. In these (and most) parts of India women beyond a certain age wear saris, which are always floor-length or, if they wish to signal their modernity, a salwar kameez (or Punjabi) with pants that fall to the ankle.

Soon we are at the syunagogue, about which more in another blog entry, and with this my afternoon in Camp is concluded. As I leave by rickshaw, I note that Camp also has its swank side. The close and vibrant streets in the part of Camp where Muslims, Jains, Catholics, Parsees and Buddhists make their home in Pune gives way to broader streets where high stone walls offer only occasional glimpses at the vast and landscaped colonial ‘bungalows’ where the more affluent outsiders of Pune village make their homes. Huge billboards advertise housing complexes complete with swimming pools, fitness centers and around-the-clock security. This world seems as foreign to the heart of Camp Kranti showed me as is the Deccan Gymkhana area where I am living. The streets again become densely packed as the rickshaw crosses out of Camp and into the heart of the old city.

Soon I will be ‘home’ at Bhandarkar Institute, one of Pune’s most venerated symbols of high brahmin culture in its fullness.

Wednesday, June 07, 2006

synagogue in pune

Last week I caught a glimpse from a rickshaw of a massive structure that my friend Kranti told me was a Jewish syngagogue. Today on our walk through her quarter, we stop by. The synagogue is surrounded by a high fence, and the watchman is firm and unsmiling as he tells us that we cannot enter. Unless we are Jewish, he will not allow us inside. We begin asking questions about the Jewish community in Pune and the synagogue’s activities, which he answers readily but still without smiling.

The synagogue was built 157 years ago and features a towering clock spire. The watchman tells us David Sassoon, who financed its construction, wanted the synagogue to be visible all across Pune, as indeed it was in its day.

The watchman himself is not Jewish, but has inherited the job of watchman from his father, and is clearly quite proud of the place. A Jew from Baghdad, David Sassoon was a major philanthropist, and built a hospital that stands to this day in Pune and bears his name. The mayor of Pune recently submitted a motion to remove the Sassoon name from the hospital and call it instead Dr. Ambedkar Hospital. The watchman tells us he had signed a petition protesting that initiative. My friend Kranti, though her family are followers of Dr. Ambedkar, tells him she too had written to protest that change. (The move was not particularly anti-Semitic, but rather part of a widespread move to rid Maharashtra of British names, and The mayor, when told of David Sassoon’s history, commented that she just thought he was British, and announced she was withdrawing her motion.)

Although Kranti has explained that I am a Buddhist nun from America, the watchman again whether I am Jewish, and it becomes clear that he would actually like to let us in. At last, he does, with a wave of his hand. We can walk around the grounds - but cannot enter the synagogue, he adds sternly.

We circle the synagogue. But for the stars of David, to my eye it looks an awful lot like a Gothic cathedral, right down to umatching ornamentation on the columns and long narrow stained glass windows.

As we come round the corner to return to the gate, we see a man and his wife enter on a scooter, and fear we may have gotten the watchman in trouble with our insistence. As we make for the gate, instead he calls us. The caretaker would like to meet us.

He opens the doorway, dons his yarmulke and invites us into the synagogue itself. We are inside an exquisitely detailed, almost understated synagogue in white marble with delicate, hand-painted trim, and all sense of Gothic cathedral disappears completely. The caretaker and his wife turn out to be long-standing members of the community and are most gracious in entertaining our questions. When I tell them I am from New York, his wife is full of questions about synagogues there. Are there really as many as she has heard? Do they offer Hebrew instruction? They are happy to answer our questions as well. The Jewish community in Pune now numbers 250 people, they tell us. Most are ‘Bagdadi’ Jews who migrated to India under British rule in the 18th century, but ten or so are Bene-Israel Jews, or Jews whose ancestors are said to have arrived in India before the destruction of the Second Temple in the first century of the common era. There had been several Jewish communities in Pune, but entire communities emigrated to Israel and now all the city’s Jews fit easily into this one space. They no longer use the separate section upstairs for women, but sit on opposite sides of the main floor during worship. All the high holidays are observed, as are services on the Sabbath, and weddings are still held in the synagogue itself. Rabbis visit, but none is resident, and there is no Hebrew instruction. Still, the foundation started by the Sassoon family continues with its charitable work, and now even has its own website - www.jacobsassoon.org - they tell us with some pride.

When it is time to leave, mindful of the watchman’s position, we make sure they know that he was very careful about letting us in, and did so only after long conversation. The caretaker tells us he used to open the synagogue for visitors for several hours one morning a week, but now will not even talk to journalists inquiring into the program. In 1990, in the opening days of the Gulf War, protestors broke into the synagogue and set fire to it. The Torah was burned, he tells us, with obvious distress. After that, they built the wall, and began to turn visitors away at the gate. Our visit ended, we return to that gate, and are treated to a broad grin from the watchman as we thank him and bid him goodbye.

The synagogue was built 157 years ago and features a towering clock spire. The watchman tells us David Sassoon, who financed its construction, wanted the synagogue to be visible all across Pune, as indeed it was in its day.

The watchman himself is not Jewish, but has inherited the job of watchman from his father, and is clearly quite proud of the place. A Jew from Baghdad, David Sassoon was a major philanthropist, and built a hospital that stands to this day in Pune and bears his name. The mayor of Pune recently submitted a motion to remove the Sassoon name from the hospital and call it instead Dr. Ambedkar Hospital. The watchman tells us he had signed a petition protesting that initiative. My friend Kranti, though her family are followers of Dr. Ambedkar, tells him she too had written to protest that change. (The move was not particularly anti-Semitic, but rather part of a widespread move to rid Maharashtra of British names, and The mayor, when told of David Sassoon’s history, commented that she just thought he was British, and announced she was withdrawing her motion.)

Although Kranti has explained that I am a Buddhist nun from America, the watchman again whether I am Jewish, and it becomes clear that he would actually like to let us in. At last, he does, with a wave of his hand. We can walk around the grounds - but cannot enter the synagogue, he adds sternly.

We circle the synagogue. But for the stars of David, to my eye it looks an awful lot like a Gothic cathedral, right down to umatching ornamentation on the columns and long narrow stained glass windows.

As we come round the corner to return to the gate, we see a man and his wife enter on a scooter, and fear we may have gotten the watchman in trouble with our insistence. As we make for the gate, instead he calls us. The caretaker would like to meet us.

He opens the doorway, dons his yarmulke and invites us into the synagogue itself. We are inside an exquisitely detailed, almost understated synagogue in white marble with delicate, hand-painted trim, and all sense of Gothic cathedral disappears completely. The caretaker and his wife turn out to be long-standing members of the community and are most gracious in entertaining our questions. When I tell them I am from New York, his wife is full of questions about synagogues there. Are there really as many as she has heard? Do they offer Hebrew instruction? They are happy to answer our questions as well. The Jewish community in Pune now numbers 250 people, they tell us. Most are ‘Bagdadi’ Jews who migrated to India under British rule in the 18th century, but ten or so are Bene-Israel Jews, or Jews whose ancestors are said to have arrived in India before the destruction of the Second Temple in the first century of the common era. There had been several Jewish communities in Pune, but entire communities emigrated to Israel and now all the city’s Jews fit easily into this one space. They no longer use the separate section upstairs for women, but sit on opposite sides of the main floor during worship. All the high holidays are observed, as are services on the Sabbath, and weddings are still held in the synagogue itself. Rabbis visit, but none is resident, and there is no Hebrew instruction. Still, the foundation started by the Sassoon family continues with its charitable work, and now even has its own website - www.jacobsassoon.org - they tell us with some pride.

When it is time to leave, mindful of the watchman’s position, we make sure they know that he was very careful about letting us in, and did so only after long conversation. The caretaker tells us he used to open the synagogue for visitors for several hours one morning a week, but now will not even talk to journalists inquiring into the program. In 1990, in the opening days of the Gulf War, protestors broke into the synagogue and set fire to it. The Torah was burned, he tells us, with obvious distress. After that, they built the wall, and began to turn visitors away at the gate. Our visit ended, we return to that gate, and are treated to a broad grin from the watchman as we thank him and bid him goodbye.

Tuesday, June 06, 2006

from the text: there are other beings here too!

Despite what is reported in this blog, most of my time here is spent reading - reading a text that can be so dazzling in its narrative details that one easily overlooks any metaphorical readings. Here is my translation of a description of the moment that Buddha (then still just a bodhisattva) was conceived.

At that time, the earth trembled greatly, and the entire world was filled by a vast light, exceeding in its intensity the hues of the 33 gods. As a sun and moon in the darkest hells of the world: so great was this extraordinary appearance; so great was its power. This vast light filled even those places that were black with a blackening darkness that has not known the light of a sun or moon. The sentient beings born there had not seen even their own outstretched arms, but by this light they now saw one another. They said to one another, “Sirs, there are other beings here, too!” And so they came to know that there were other beings there too.

- Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinayavastu (Pravrajyāvastu)

This image itself is startling in its beauty, even without contemplating the implication that the experience of suddenly discovering that one is surrounded by others is being understood as one of the effects of the Buddha’s presence in the world.

At that time, the earth trembled greatly, and the entire world was filled by a vast light, exceeding in its intensity the hues of the 33 gods. As a sun and moon in the darkest hells of the world: so great was this extraordinary appearance; so great was its power. This vast light filled even those places that were black with a blackening darkness that has not known the light of a sun or moon. The sentient beings born there had not seen even their own outstretched arms, but by this light they now saw one another. They said to one another, “Sirs, there are other beings here, too!” And so they came to know that there were other beings there too.

- Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinayavastu (Pravrajyāvastu)

This image itself is startling in its beauty, even without contemplating the implication that the experience of suddenly discovering that one is surrounded by others is being understood as one of the effects of the Buddha’s presence in the world.

Saturday, June 03, 2006

arranged marriages

A German friend here of mine who is also studying in Pune recently returned from a wedding of an Indian friend she had met in Europe, while he was there on an assignment.

The wedding was large. Very large. Some 2,500 guests were invited to the main event. A more intimate gathering of 500 people attending the remainder of the activities surrounding the wedding. There was also a special event for their Hindu guests, an affair attended by 500 of their Hindu friends who were feasted at a banquet hall featuring vegetarian food. Only the very closest 100 or so relatives and family friends would have the privilege of being hosted in and around the house itself, and would take their breakfast, lunch and dinner together at the house. During the five days of the wedding festivities, meals would be cooked, gifts would be given to guests and received in carefully prescribed patterns of exchange.

In short, there was much to be done. My German friend spent most of her time joining in the work with her host’s female relatives, as men and women live largely separate existences. One evening, she had some time to chat with her host, the groom. In Germany, when she had casually asked whether he had a girlfriend, he said yes, a girl in Mumbai, She now asked him whether the bride was that same girl. No, he said. It was the custom of his people to marry cross-cousin. He and his bride-to-be had known each other as children, but lived in villages some four hour’s bus ride apart. In any case, since girls and boys are segregated from the age of 15, they had not had any interaction in years. She had not seen him since then, though unbeknownst to her, he had paid a visit to her village to get a glimpse of her as the marriage negotiations advanced. The girl in Mumbai had not even been considered as a prospective bride. My German friend struggled with her reaction to that. She told me she recognized that her impulse to condemn what she saw as the lack of personal choice and human feeling in this arranging of marriages did not fit well with her observation that the women in the extended family seemed remarkably contented with their lives.

Attempting to help her understand the choices involved, her host said:

“You see how little time I have to spend with you here. Just a bit at the end of the day. It will be basically like that with my wife. The rest of the time, she is with the women of my family. She isn’t marrying me, actually. She is marrying my family. If my mother doesn’t like her, her life will be awful. And if she is not one of my cross-cousins, the rest of the village won’t accept here either, and her life here will be a hell. It wasn’t for myself that I didn’t marry my friend in Mumbai. It was for her. For her happiness.”

Later, when it was time for the bride to leave her childhood home and family to depart for the wedding and the home she would now share with her husband, the entire family wept bitterly. The family had actively arranged for this marriage, and yet they wept when their plan was at last executed. I imagine that at such moment, what my friend witnessed was a rare glimpse at the high value placed on this invisible web that held together that single household, and how highly valued was the sharing of all the small and quiet moments of that household’s life. When the moment came for the bride to leave home, even the men of her household were openly shedding tears, and visibly pained at her departure. My German friend asked them later why they wept so, since as the wife of a cross-cousin they would still see her and she would still be part of the extended family. “Yes,” they said, “We will see her. She will still be part of our family. But she is leaving our house.” She is leaving our house.

The wedding was large. Very large. Some 2,500 guests were invited to the main event. A more intimate gathering of 500 people attending the remainder of the activities surrounding the wedding. There was also a special event for their Hindu guests, an affair attended by 500 of their Hindu friends who were feasted at a banquet hall featuring vegetarian food. Only the very closest 100 or so relatives and family friends would have the privilege of being hosted in and around the house itself, and would take their breakfast, lunch and dinner together at the house. During the five days of the wedding festivities, meals would be cooked, gifts would be given to guests and received in carefully prescribed patterns of exchange.

In short, there was much to be done. My German friend spent most of her time joining in the work with her host’s female relatives, as men and women live largely separate existences. One evening, she had some time to chat with her host, the groom. In Germany, when she had casually asked whether he had a girlfriend, he said yes, a girl in Mumbai, She now asked him whether the bride was that same girl. No, he said. It was the custom of his people to marry cross-cousin. He and his bride-to-be had known each other as children, but lived in villages some four hour’s bus ride apart. In any case, since girls and boys are segregated from the age of 15, they had not had any interaction in years. She had not seen him since then, though unbeknownst to her, he had paid a visit to her village to get a glimpse of her as the marriage negotiations advanced. The girl in Mumbai had not even been considered as a prospective bride. My German friend struggled with her reaction to that. She told me she recognized that her impulse to condemn what she saw as the lack of personal choice and human feeling in this arranging of marriages did not fit well with her observation that the women in the extended family seemed remarkably contented with their lives.

Attempting to help her understand the choices involved, her host said:

“You see how little time I have to spend with you here. Just a bit at the end of the day. It will be basically like that with my wife. The rest of the time, she is with the women of my family. She isn’t marrying me, actually. She is marrying my family. If my mother doesn’t like her, her life will be awful. And if she is not one of my cross-cousins, the rest of the village won’t accept here either, and her life here will be a hell. It wasn’t for myself that I didn’t marry my friend in Mumbai. It was for her. For her happiness.”

Later, when it was time for the bride to leave her childhood home and family to depart for the wedding and the home she would now share with her husband, the entire family wept bitterly. The family had actively arranged for this marriage, and yet they wept when their plan was at last executed. I imagine that at such moment, what my friend witnessed was a rare glimpse at the high value placed on this invisible web that held together that single household, and how highly valued was the sharing of all the small and quiet moments of that household’s life. When the moment came for the bride to leave home, even the men of her household were openly shedding tears, and visibly pained at her departure. My German friend asked them later why they wept so, since as the wife of a cross-cousin they would still see her and she would still be part of the extended family. “Yes,” they said, “We will see her. She will still be part of our family. But she is leaving our house.” She is leaving our house.

Thursday, June 01, 2006

the rains come

Summer in my corner of India has been severe but swift, and ended overnight with the coming of the monsoon. The first drop of rain I had seen in the two months since I arrived in Pune came last Friday, the afternoon of the Khandoba puja (see May 27 blog entry). Pune had been remarkably green, given the utter absence of rainfall, but still it is dry. So much so, in fact, that clothes can be hung two or three shirts on top of another, and still be bone-dry in a few hours, if there is not enough space to hang them one by one, as can happen when Anna and I both have our laundry hanging on our veranda at the same time.

Summer in my corner of India has been severe but swift, and ended overnight with the coming of the monsoon. The first drop of rain I had seen in the two months since I arrived in Pune came last Friday, the afternoon of the Khandoba puja (see May 27 blog entry). Pune had been remarkably green, given the utter absence of rainfall, but still it is dry. So much so, in fact, that clothes can be hung two or three shirts on top of another, and still be bone-dry in a few hours, if there is not enough space to hang them one by one, as can happen when Anna and I both have our laundry hanging on our veranda at the same time.When this first bout of rain fell, it was not a major downpour, but it was certainly wet, and the temperature plummeted instantly. I was inside working at my desk, from time to time glancing out the window that lies directly before my desk, when I heard a rustling behind me. One of the young boys from the village behind the institute was huddled just inside my doorway. The roof of the veranda provides shelter from the rain, so there seemed no practical need for him to enter my room. As I turned to look at him, he smiled and gestured that he was there hiding from his playmates. He respectfully took off his sandals, set them down inside the door and returned to the urgent business of waiting for his friends to find him. He could barely suppress his giggling. I have two doors to my room, one letting into the main stairwell and the other letting out onto the veranda, and when the shout of his friends revealed that they had located him, he took off with a dash through the other door, leaving his sandals behind and saying, “Sorry, madam, ok?” as he crossed my room. Two of his friends tore through my room in mad and noisy pursuit, nearly knocking over my fan as they went. “Sorry, madam!” they shouted, leaving a thick trail of mud across my floor.

When the monsoon does not come, or comes in small measure, there are drought, famine... and desparate suffering. When the monsoon comes in its fulness, the fields are long with grain, the trees heavy with fruit. Even shorter term, the coming of the monsoon brings relief from the dry and dusty heat, and signals the season of growth, and green, and vibrant life. In fact, the exuberance of the young boys playing hide-and-seek in my room seems the most suitable response. But still this was not the monsoon, just a little pre-monsoon shower. The real rains came three days later, and when they did they snuck up on us in the dark of night.

I was awakened at about 1:30 am by bursts of lightning, puncturing the darkness with longer repetitions than I recall seeing anywhere else. The repeated lightning bolts were followed by long and continual rumblings of thunder, as if a plane were right just overhead, but hovering and not passing. The winds slammed my windows shut. They rattled and opened again from time to time, and I did not until then realize that they could not be latched properly. After a while I went back to sleep, until one particularly energetic burst of thunder roused me again. I counted the seconds from flash to thunder, and determined it was some 30 miles away. Still, the electrical outlets were clustered just above my head, so I got up and unplugged everything. I disconnected even my fan, which had been rendered unnecessary by the drop in temperature to a downright chilly 79 degrees. Again to sleep, and so it went until somehow my sleep was reluctantly penetrated by the recognition that the sound of rain falling was coming from inside my room. As I got up to investigate, my feet brushed a large wet spot at the end of the mattress. Apparently I was sleeping under one of several major leaks in the ceiling. By now, it was 4 am and quite tired. I simply shifted my bed out of harm’s way, took everything up off the floor, put a bucket under where I thought the main drip was, and went back to sleep, careful to rest my feet to the side of the wet spot.

The next morning, I awake, survey the damage and note that there are large watermarks fanning across my ceiling. With the monsoon’s persistent dampness, a generous spread of mold cannot be long away. I leave this room next week, but it is jarring nonetheless to recognize that my cozy little home has become virtually uninhabitable overnight.

Once I have fulfilled my duty to describe my disaster in detail and show the damage to all my neighbors and passersby, I take myself out for a walk. Dodging puddles and breathing in deep the cool morning air, I suddenly realize that the world now smells different. Fresh and full of earthy aromas, unidentifiable yet oddly familiar to me. The air is filled with hundreds of winged creatures I had never seen before, their four wings pale and lacy and yellow. Birds in clusters seem to have decided to all pay our garden a visit at the same time. The sky hangs low now with moody but delicate clouds, casting an oddly gentle light on this world of fresh new life. The monsoon has arrived in Pune.

Monday, May 29, 2006

sneak preview of sarnath

daily rhythms

My life in Pune has taken on a rhythm of its own, dictated by weather as much as by my study demands. April and May are summer here, and we are just coming to the peak of the hot season. I am out of bed by 6:30, and immiedately open all my doors so the room can cool down before the sun heats things back up. It has been about 90 degrees at night in my room, though I sleep with the window open. It cools down to 85 or 86 in the morning - and even less these days as we moved into the pre-monsoon period. Once the sun starts to flood my room, I shut everything - windows and doors - and close the curtains, which I bought especially for this purpose. By 7:30 I have had breakfast, and then I plunge into my text. I have been translating from 7:30 or 8 until 1 am daily, then lunch, or tiffin, which is delivered to my room. At 1am on the dot the electricity goes out - we have scheduled daily outages to allow for load sharing across the power grid. This means no fan and a full stomach, so often I just rest for a bit. Then, sometimes (when he has time for me) I read with MG Dhadphale, professor emeritus of Pali and Sanskrit at Fergusson College here in Pune, and currently head of the very venerable old Pune Sanskrit research institute, Bhandarkatr Institute.

After that, I turn to Sanskrit study in general - memorizing more vocabulary and working through the Paninian grammar that my Sanskrit professor in Visakhapatnam, Prabhakara Shastri, is composing. In the evenings, I open the doors once it is cool again to help bring down the temperature, and at 10 i call Professor Shastri and he quizzes me and gives me more assignments to work on for the next day.

I have a neighbor named Anna who is an anthropologist from Vienna studying female priests (purohitas) and she very wisely feels I should explore the city more (see below for one successful effort on her part to get me to go out more!)

On Sundays I try to take the morning off, and we go to visit a local temple or market. Anna is here with her four-year-old son Christopher and ten-month-old daughter, and Christopher likes to visit when my doors are open. He speaks to me in German which i only sometimes can understand and I answer in English. We get along exceedingly well. He brings bits of his snacks and fruit to me, and I share with him my peanuts. Last week he put his hands around my arm and said, 'wir sind freunde' - we are friends.

After that, I turn to Sanskrit study in general - memorizing more vocabulary and working through the Paninian grammar that my Sanskrit professor in Visakhapatnam, Prabhakara Shastri, is composing. In the evenings, I open the doors once it is cool again to help bring down the temperature, and at 10 i call Professor Shastri and he quizzes me and gives me more assignments to work on for the next day.

I have a neighbor named Anna who is an anthropologist from Vienna studying female priests (purohitas) and she very wisely feels I should explore the city more (see below for one successful effort on her part to get me to go out more!)

On Sundays I try to take the morning off, and we go to visit a local temple or market. Anna is here with her four-year-old son Christopher and ten-month-old daughter, and Christopher likes to visit when my doors are open. He speaks to me in German which i only sometimes can understand and I answer in English. We get along exceedingly well. He brings bits of his snacks and fruit to me, and I share with him my peanuts. Last week he put his hands around my arm and said, 'wir sind freunde' - we are friends.

Sunday, May 28, 2006

night out in pune - possession and puja

(May 27, 2006) - Last night my neighbor Anna, the Austrian anthropologist came knocking urgently on my door. "Come," she said, "there is a puja just starting out back." I had just sat down to do some writing on the 'What Am I, a Demon"?" story cycle in the Vinayavastu. When she saw that I was not jumping up at once, she spoke again, more firmly this time: "Just come, now." So I did.

Earlier in the week, there had been a marriage in the tiny village behind our building. The village is comprised of housing for the staff - watchmen, clerks and lower-level employees of Bhandarkar Institute - and thus I know several of its residents by face, if not by name.

It is now four days later, still the wedding rituals linger on, and each day there is some fresh activity that both extended families gather and attend. Tonight was planned a puja to Khandoba, a deity who appears to take the form of a heavy metal chain. This particular puja is an a regular part of the cycle of wedding rituals for this group, and would be followed by a meal and then a nightlong program involving song and dance to the deity. Those attending were planning on staying up all night to participate. The puja began at about 9pm, ordinarily enough, with red kumkum and yellow turmeric powder, lights, and other offerings for the deity. The altar was on the bare ground, a cloth placed under the chain, and the offering substances arranged on plates. A torch that looked like a ritual implement was blazing, and waved at various junctures in the ritual. Two pujarins (ritual officiants) were there, dressed in white with a white cap. The groom was dressed similarly, with his wife at his side in a splendid silk sari with elaborate jewelry and makeup. They and the married couple crouched by the altar, while everyone else stood around watching as the pujarins directed the series of ritual actions that had to be performed. A small band of musicians, heavy on the percussion, were on hand, offering music. With the musicians was a young woman dressed in a fairly ordinary sari, with only the usual jewelry and make-up. We were told she would dance for us later in the evening. She stuck close to the musicians and made no contact with anyone else.

As I joined her in the circle of onlookers, Anna whispered to me that this was a puja brahmins would not hold nor most likely attend. As she did I noticed that one of the middle-aged ladies - a relative of the groom - had begun dancing, her body jerking somewhat violently as she did. Two women approached her from behind, quickly untied her hair and adjusted her sari, with the end being tucked firmly into her beltline. At this point, we may have been 15 or 20 minutes into the puja. Then another woman began to dance, this one quite frail and elderly: the bride's grandmother. Her movements were vigorous and rhythmic as she danced. Her bun too was let down and, with a minimum of fuss, her sari adjusted and secured around her waist. I guessed this was to protect the women from immodesty as they move about. Then a third woman began to dance: the groom's grandmother. At least initially she appeared to retain some measure of control, for when they came to undo her hair, she waved them off firmly. She had her hair coiffed a bit elaborately, and they left it untouched at her request, but they did readjust her sari for her. She danced with rather more decorum than the other two.

During this puja, no other women danced, and people gave the three of them plenty of space. About 20 to 30 people had gathered around, and they now stood in the dim light of the torch, watching the dancers rather causally, without particular awe or concern. Some people talked quietly as the music continued.

All three women danced facing the altar, though as was clarified later by the bride's sister, the women were not dancing. Certainly her grandmother would never dance in public. Rather, the goddess was dancing.

Later the bride's grandfather told us that when they had held the Khandoba puja after the wedding of the bride's father, similarly a grandmother of the bride and a grandmother of the groom had also become possessed by the goddess and danced. The family had a special connection to the goddess in a number of forms, and one of these would likely have been present. It was very possible that when the next generation marries the goddess might choose their grandmothers to dance as well.

From time to time, some women went to the altar, took some of the red kumkum powder that is offered in worship to deities, and anointed the women's foreheads with it. I understood them to be doing so as an offering to the goddess as she danced.

Very shortly after the dancing began the music stopped and did not resume until they had returned to themselves. The musicians had allowed the three to dance for no more than 10 minutes, and clearly meant the possession to end, waiting until the women emerged form that state. Each did so in a bit of a daze, as if awakening form a deep sleep. Their eyes were glassy. Two of them took the ends of their saris and wiped the kumkum powder from their foreheads. They remained standing where they had been. The drumming and ritual continued for another 15 or 20 minutes. The bride and groom stood always side by side, woman on the left. They were made at times to offer some substances to the altar, at others to carry them off in a particular direction indicated by the pujarin. At one point, the chain was lifted with great care, a cloth draped around the groom's neck and the chain placed on top of it. In this way, he circled the altar holding a leaf pouring water as they went, and followed by five of the young girls from the village who did likewise. They made a ring of water around the altar had been, and continued in a small procession up to the groom's home. The puja continued inside the house at the family altar but at this point most everyone seated themselves to chat on mats outside the house, where a large and elaborate altar had been constructed of tripods of five sugar canes and many other objects I was less able to identify. After some time, food began being carried out on leaf plates and all had to stand so that all could be re-seated in proper seating order for eating. Very unusually, women were served food first, an inversion of the normal order that happens only at this puja.

I left at this time, partly to avoid the social discomfort of not partaking of the food, and also because at this time, I was to call my Sanskrit professor in Vishakhapatnam, Prabhakara Shastry. When I did, he strongly encouraged me to attend every single function I was invited to, as well as those to which I had not been invited, but where my presence would not be offensive. He said he had done the same in the States, entering churches where weddings were in progress if it seemed he was not prohibited from attending.

Anna had come home to put her children to sleep and rest for bit herself, as the program of song and dance was to begin at 11:30, we had been told, and would last all night. At about midnight I began to hear drumming and roused Anna from her sleep. Anna's four-year-old son Christopher had very much wanted to see it, and had asked her to wake him up and take him there. I pushed Christopher in his stroller, Anna carried her sleeping 10-month old daughter in her arms, well and thus the four of us thus went out together to the groom's house, where the night's events would take place.

When we arrived, everyone was already seated, the female relatives of the groom all together in the spot directly facing the musicians, but on the other side of the altar. In my estimation, this women's mat was by far the best spot to watch the evening's events. The female relatives of the bride also sat together on a map, off to one side. The men were divided into groups, and sat farther from the altar. One group seemed loosely, but only loosely, comprised of the groom's relative, the other the bride's. We were all accommodated under the cover of a decorative canopy that had been erected for the event. Another set of men, mostly older, sat on beds that had been placed outdoors, outside the canopy and at a remove from the center of the activities. The wedding was a bit unusual perhaps in that both groom and bride hail from this same small cluster of houses, so most everyone seemed to know each other well.

When we arrived the band was playing, and just as we were arriving, one of the three women who had earlier been possessed again stood to dance. Again she faced the altar, again she alone danced, and again her hair was let loose and her sari made tighter. She was dancing near one of the poles that held up the tent we were under, and two women hovered near her to intercede should her movements bring her too near it. Again women came to anoint her forehead as she danced, but this time the dancing was permitted to continue for a bit longer than previously, but finally, the band stopped playing, evidently sparking an end to the state she was in. One of the women who had been hovering nearby stepped closer, just at the moment when the woman possessed fell to the ground. The second woman was brought down with her, occasioning a great deal of laughter on the part of this second woman as well as those surrounding her. Those sitting around the two fallen women exchanged smiles or laughed at this bit of slapstick, most of all the woman who had been sent tumbling when the possessed woman fell who seemed to seek out eye contact with other women to grin at what had transpired. The woman who had danced possessed did not initially join in the laughter, but rather sat a bit dazed. After a couple of minutes, though, after wiping some of the kumkum and sweat from her face, as she returned to herself, she too exchanged smiles with one or two other women who caught her eye. I was struck by the comfort in shifting from the serious work of dancing for the goddess and caring for the woman who did so with the playful laughter at the slapstick fall.

Meanwhile, the drumming resumed. The musical accompaniment featured mainly drumming with cymbals though one string instrument and a sort of accordion were also at hand. All the musicians were male, and all provided vocal support, in songs that seemed to draw heavily on call-and-response. To my utterly untrained ear, it did sound rather African.

Another woman, one of the grandmothers again, became possessed but did not stand to dance. Instead she threw the upper half of her body forward and back, and side to side, rhythmically in powerful jerks. Someone unloosed her hair, and she was allowed to continue thus for some time. People watched from where they sat, but she was not made particularly the center of any attention. No particular fuss was made, and it all seemed fairly matter-of-fact. Again the goddess seemed to leave her when the music stopped, and she sat for some time, disconnected from those around her and seeming somewhat disoriented.

This was the last of the five instances of possession I saw that night, all happening in the first quarter of the evening's activities.

From time to time, people randomly came forward, men as well as women, and picked their way between the musicians to make a cash offering or offering of kumkum and turmeric at the altar. A couple of older women carried around the tray of powders and anointed the foreheads of the women seated. Throughout, people came and went, younger people continually shifting from group to group, some going off to sleep, while others simply stretched out on the mats and dozed off for a bit. For a while, young girls brought around trays with small cups of strong chai, for those who were choosing not to sleep.

After some time, the format shifted, and two of the musicians began what sounded to me like a ritualized form of banter, half sung and occasioning much laughter. The language was too hard for Anna to follow, and one of the girls seated near us was only able to indicate that it was about different gods. I imagined it to be some form of ritualized rivalry. This went on for quite a while, with the older man dancing in what seemed to me a female style of dance. One of the young girls, Diksha, eleven years old and by far the best dancer in the crowd, stood and joined him. They stood dancing about five feet apart. The man, about sixty years old, kept shifting dance styles and she watched each shift, smiling, and copied his moves. She clearly enjoyed herself but was called back to sit down after a couple of songs. The song, dance and banter continued and later when the performers were calling her to dance, her mother said no. The girl with some English explained that it was not proper for her to dance with him - and in fact had not been proper earlier either, as she was female and already too old for that.

Next to come forward to dance was the single female in the group of entertainers. Until now this young woman had been milling around near the musicians, not interacting with anyone in the audience. At this point, though, she began to dance with the older man, again at a respectable distance from him, facing him, in a style different from any I had seen before. Her hands were continually moving in patterns reminiscent of classical Indian dance, but much more erratic and rapid. Her hips and shoulders moved in small jerks, and she never varied her movements. She did not strike me as a particularly skilled dancer. Men would come forward to dance with her - mostly unmarried men in their early twenties, and many danced in a wild style with big Bollywood movements that only men get away with off-camera here. On one occasion, one such young man came in closer to the woman and the lead musician intervened, calling out loudly in his singsong bantering style that that was her side, and the man must stay over there, on his side. This occasioned much laughter.

It was noted that the groom had gone off - it was 2 am or so at this point, and he had slipped off to sleep a bit - and he was called back. His bride too, who had already been called back from sleep once earlier, was also made to return, and watched as her husband was made to dance with the female performer.

Again the format shifted, with people offering money to the performers - usually about ten rupees - and telling them a name, with the understanding that the performers would then poke fun at them. those in the audience who offered cash for this service were mainly men, and it went back and forth it went, with men from either side of the altar . One of the younger musicians would collect the cash, bring it to the performer who had the main role in the banter, and half-whisper the name of the next victim. The senior performer immediately called out that name, weaving it into his singing. With one exception, those singled out for such ribbing were all men. At times, the person called was not present, and someone went off to rouse them from their sleep in one of the houses nearby. Their obvious grogginess as they were brought forward invariably occasioned much amusement.

For those singled out, the ribbing consisted in part in having to come forward to dance with the woman. Many of the men, especially those a bit older, were clearly embarrassed at having to perform publicly and some did their best to refuse, though in the end, all those singled out were made to take a turn, however short. Before they approached her to dance, though, their faces were anointed, often very thoroughly, with turmeric powder, red kumkum powder and a black powder. Often they ended up painted garishly in these three colors, their face and, inevitably, clothes, stained yellow by the turmeric.

Next to the altar, a fire had been built, and someone sat tending to it, feeding it ladlefuls of oil regularly. As part of the ribbing, the man called forward first had his face painted, usually while seated here. On occasion, one of the young men in the audience would come and restrain their hands, the better to paint them fully. Turmeric might be dusted into the hair, and in one instance, even put under the man's shirt. Sometimes they stood up immediately and danced with the woman, before rushing back to their seat, but others, especially younger boys and brothers of the bride or groom, might sit and tend this fire for some time as well. They may have done more while seated here, but I could not see clearly from where I sat with the groom's female relatives.

This was all done with much joy, and amidst great laughter, and though I could not follow the banter that sparked outbursts of laughter, I found myself grinning often. At one point, someone gave Anna's name to the musicians and they seemed intent on getting her to come up to dance - something no female except Diksha had done. They told her no problem for women to dance, and she joked with them a bit. The women were laughing too, but a few of this sitting near us said, "No Anna, you must not dance." Anna joked that she would certainly dance, but as the last women to do so, after all the other women had had their turn, and when they saw that indeed she would not dance, they turned their attention elsewhere, smiling as they did.

The dancing continued, and at one point many of the younger children still awake joined in the fun, forming a crowd near the altar. The female performer quietly stepped aside and stood watching.

At a certain point, the musicians took a break, and one of the younger ones carried the tray of powders around and anointed the audience members' foreheads. When they came to me and Anna, they quite respectfully determined whether we were each willing before placing the red powder on her forehead.

After this, the musicians who had been standing this entire time, seated themselves and played on from the ground. The dancing and bantering stopped at this point, and the energy level dropped as well.

During the evening, various children (girls and boys) and women came wanting a turn to hold Anna's small daughter Ria, and one such woman, whom Anna did not know, succeeded in putting her back to sleep. Once asleep, Ria was carried into the house and placed on a mat to sleep, next to some other small children. Anna's son Christopher initially could barely stay awake, but later became quite engaged in the activities. He stood up to dance at one point - his dancing consisting in standing motionless with one arm in the air in the pose that dancers often adopt as they move about. He was given a turn to have his face painted, which was done fairly sparingly. We had made small moves to leave earlier, but one elder relative had motioned to us to stay a bit longer. But now Christopher was becoming cranky and her daughter had awakened again, and we left shortly before 4 am, less than an hour before the activities ended.

As Anna and I filed out, each of us with one of her two children, the lead musicians were calling out something that included the word 'deva' (god) and each folded their palms towards me in prostration as I left.

Earlier in the week, there had been a marriage in the tiny village behind our building. The village is comprised of housing for the staff - watchmen, clerks and lower-level employees of Bhandarkar Institute - and thus I know several of its residents by face, if not by name.

It is now four days later, still the wedding rituals linger on, and each day there is some fresh activity that both extended families gather and attend. Tonight was planned a puja to Khandoba, a deity who appears to take the form of a heavy metal chain. This particular puja is an a regular part of the cycle of wedding rituals for this group, and would be followed by a meal and then a nightlong program involving song and dance to the deity. Those attending were planning on staying up all night to participate. The puja began at about 9pm, ordinarily enough, with red kumkum and yellow turmeric powder, lights, and other offerings for the deity. The altar was on the bare ground, a cloth placed under the chain, and the offering substances arranged on plates. A torch that looked like a ritual implement was blazing, and waved at various junctures in the ritual. Two pujarins (ritual officiants) were there, dressed in white with a white cap. The groom was dressed similarly, with his wife at his side in a splendid silk sari with elaborate jewelry and makeup. They and the married couple crouched by the altar, while everyone else stood around watching as the pujarins directed the series of ritual actions that had to be performed. A small band of musicians, heavy on the percussion, were on hand, offering music. With the musicians was a young woman dressed in a fairly ordinary sari, with only the usual jewelry and make-up. We were told she would dance for us later in the evening. She stuck close to the musicians and made no contact with anyone else.